1. Introduction

This dossier focuses on the terminology and practices concerning sesame cultivation in Babylonia during the Old Babylonian period. Letters between officials and kings and the personal correspondences of individuals describe particular or unusual situations in managing different economic and agricultural activities. This documentation helps us understand the chaîne opératoire of sesame cultivation and production by qualitatively evaluating data with termini technici. Some legal and administrative texts provide quantitative data and information about sesame cultivation’s periodicity and sesame harvest management. For a summary of sesame cultivation in the Old Babylonian period by places and periods, see Dossier A.1.1.13. For a detailed view of sesame cultivation in Mari, see Dossier A.1.1.14.

2. Terminology for Sesame and Sesame Cultivation

2.1. Sesame (Seeds)

Attested in the cuneiform documentation since the Sargonic Period (see Dossier A.1.1.23), sesame was indeed introduced from India. In the historiography, there were supporters of an identification of the “oil plant” with flax (Linum usitatissimum)1Helbaek 1966, CAD Š/I s.v. šamaššammū. and with sesame (Sesamum orientale)2Kraus 1968 a, Charles 1985, Waetzoldt 1985, Stol 1985, Postgate 1985, Bedigian 1985, Bedigian 1998, Bedigian 2000, Bedigian 2004, Bedigian/Harlan 1986, Powell 1991, AHw s.v. šamaššammū.. According to both philological and palaeobotanical evidence, there is no doubt nowadays that šamaššammū means “sesame” and not “flax” (Sumerian gada, Akkadian kitûm). For more details on this debate, see Reculeau’s synthesis article (Reculeau 2009: 13-22) and Bedigian’s book on sesame (2010: 4-5).

In Babylonia and Southern Mesopotamia, sesame seeds are primarily referred to by the logogram še.giš.i₃, Akkadian šamaššammū[glossary=šamaššammū]. In Northern Mesopotamia, the Middle Euphrates region (Mari[geogr=Mari], Qaṭṭarā[geogr=Qaṭṭarā], Šubat-Enlil[geogr=Šubat-Enlil], Tuttul[geogr=Tuttul]), and the Diyala region, “sesame seeds” is written with the logogram še.i₃.giš, as Stol 2011: 400 noted. These two logograms refer to both sesame seeds and the cultivated plant. Sesame appears to be the “oil plant” par excellence, as opposed to fats of animal origin, written only by the logogram for oil/fat (i₃) followed by the name of the animal from which the fat is produced.

2.2. Sesame Seeds for Sowing

While the logogram še.giš.i₃ can correspond to both sesame plant and seeds, another expression is documented for sesame seeds for sowing. A letter from the Babylonian Kingdom (AbB 14 120) mentions “sesame seeds (for sowing)” (numun še.giš.i₃). An administrative text from Mari (T.340) says a similar phrase, “sesame of the sowing (season)” (še.i₃.giš numun.a). The logogram numun (Akkadian zērum) “seed” is an apparent reference to seeds used for sowing. Harvested sesame seeds or the different states of sesame obtained during oil production are clearly differentiated from sesame oil (logogram i₃.giš, Akkadian šamnum; see Dossier A.1.1.22).

2.3. Different Qualities and ‚States‘ of Sesame Seeds or ad hoc Descriptions?

No qualities, states or kinds of sesame seeds were distinguished prior to harvesting. The sesame seeds were identified only once harvested according to their state or condition. For example, the term “average quality” (gurnum[glossary=gurnum]) is well known in the Old Babylonian documentation (ARM 22 276, OECT 15 219, YOS 5 204) to describe the sesame (Stol 1985: 120, CAD G s.v. and AHw s.v.; see for more details A.1.1.21). For an analysis of gurnum-, dikkūtum-, sīkūtum– and halṣum-sesame in Mari, see in particular the commentary of ARM 22 276 and the Dossier A.1.1.21. See also the Dossier A.1.1.22 for halṣum-sesame.

In a letter (AbB 09 127) from Alammuš-nāṣir’s Archive (from Damrum[geogr=Damrum], Samsuilūna’s reign), Alammuš-nāṣir asks his intendant Nabi-Šamaš to manage the sesame after the harvest. The total of sesame is described as “thick” (kabrūtum). Likewise,

In an administrative text from the Royal Archives of Mari, concerning king’s meals, sesame is described as “wet” (duru₅, raṭbūtum in ARM 11 077). Still, it is the only reference in the Old Babylonian documentation to our knowledge. In this case, it seems that šamaššammū raṭbūtum “wet sesame”, is a clear reference to a sesame which was wet or soaked, especially for a cooking preparation to be served at the king’s meals.

2.4. Sesame Cultivation

2.4.1. “To Do Sesame”

In Old Babylonian texts, the cultivation of sesame is usually referred to as “to do sesame” (šamassammī epēšum, AbB 01 102, AbB 01 123, AbB 05 176, AbB 14 163, BE 6/2 124, YOS 12 543) as Stol 1985: 120 pointed out. Some texts mention the related expression “a place where sesame was done” (nēpešēt šamaššammī: BIN 07 056, TCL 11 188).

2.4.2. “To Cultivate”

The general Akkadian term erēšum, “to cultivate” (AbB 14 163, TLB 04 079) can also be used for sesame cultivation, as well as the abstract term “cultivation” (errēšūtum; BIN 07 177). These terms are not specific to sesame cultivation but concern other cereal crops such as barley (on this issue, see infra).

3. Periodicity of Sesame Cultivation

3.1. The Issue of “Early Sesame”

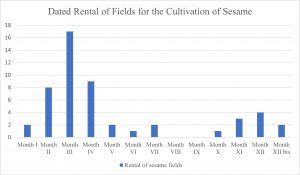

Stol, analyzing the dates of sesame field rentals and considering Iraqi ethnographic data Lebon 1964, observed that there was a “peak” in Months II/May-IV/July, but also in Months XI/February-XII/March (Stol 1985). However, as the author indicates, the dates of rental of these sesame fields appear as terminus ante quem, not terminus post quem. Therefore, there is no indication that the dates inscribed on documents corresponded to the time of sesame cultivation, as these texts may have been written before this activity.

Graph 1. Month Dates of Field Rent Contracts for Sesame after Stol 1985: 119

The data collected by Stol show that these contracts were written throughout the year, except for the sesame harvest period in Months VIII/November and IX/December. From the analysis of 54 dated rental of sesame fields texts, he deduced there must have been an “early sesame” sown in winter and a “normal sesame” planted in spring (see also Stol 2011: 401). Indeed, Stol 1985: 119 and note 5 observed that a Standard Babylonian menology from the first millennium (CT 39 20: 137) mentions še.giš.i₃ nim₂, nim₂ as a logogram for ḫarpum “early” on the root ḫrp which means “to be early” (CAD H, s.v. and AHw, s.v). He also noted that the root was attested to in a letter from Mari in connection with sesame (ARM 13 039), following Birot (Birot 1964), who edited first the letter and considered that the term ḫurrupum derived from this root.

Afterwards, Durand pointed out in his commentary of his own edition of the letter that ḫurrupum is a deverbative on ḫarpū “autumn” (AHw s.v. contra CAD s.v.) and not an indication of an “early sesame” (Durand 1998: 569-571). However, Reculeau 2009: 29-32 assumes the term ḫarpum/ḫarbum is more related to the hoe in Mari texts and thus to an agricultural technique rather than the early nature of sesame (see below). Indeed, Reculeau thinks that understanding ḫurrupum as an ‚autumn‘ agricultural operation would be contradictory to the fact that the text refers to work in the fields of a summer cereal. The process in question must have occurred during or shortly after sowing, which took place in late spring or early summer. According to Reculeau, this would be a preparatory ploughing operation (ḫurruBim ḫarāBum), similar to the expression mayyārī maḫāṣum (see below).

Consequently, there is no evidence that an “early sesame” could have existed in Mesopotamia in the Old Babylonian period. Thus, we cannot use the Iraqi ethnographic data collected by Stol; they also concern modern techniques (dependent on water reservoirs and dams). In addition, Reculeau provides arguments related to the flooding of the Euphrates in antiquity and in contemporary times, highlighting the fact that the agrarian rhythm must have been different (Reculeau 2009: 30-31).

However, at least for Babylonia, two Babylonian letters might qualify this statement. Stol spotted the letter JCS 17 82 8 published by Goetze 1936: in this missive, the sender Aḫam-arši explains to the homonymous addressee Aḫam-arši that the barley harvest (eṣēdum) did not go as planned (? — broken verb). So he has to cultivate 1 būr (6.48 ha) of a field with “ḫarpum-sesame” (šamaššammī ḫa-ar-pa-am). Referring to Landsberger 1926, Goetze had translated the expression as “early sesame”. LAOS 1 047, a letter from Kiš sent by Qurdūša to Bēlšunu, edited by Sallaberger 2011, is interesting in this regard: the sender indicates that he did not get any barley this year and, consequently, he has to cultivate sesame; it is clearly stated that the field has to be “cultivated a second time with sesame” (t[aš]ni eqlam šâtu šamaššammī epuš), in connection with the term ḫarpum. Indeed, Sallaberger translated the following sentence, šamaššammū ša tēpušu lū ḫarpū as “Der Sesam, den du (dann) angebaut hast, sei früh!” and thus understood the term ḫarpum as meaning “early”. Sallaberger linked LAOS 1 047 with AbB 14 082, in which Bēlšunu answers Qurdūša (same protagonists; see Sallaberger for prosopography) and quotes Qurdūša’s words: “Plant 9 acres (= 3.24 ha) of a field with sesame! As you know, I did not get any barley this year and (therefore) don’t be negligent to plant the field with sesame!” Given the context of these two letters, i.e. that the grain season was bad and/or that sesame must somehow compensate for the lack of barley, sesame is “early” in this case. Sallaberger considered that sowing should occur around Month XII/March, thus before barley harvest. Since the vegetation period of sesame is estimated to be about 3 months, harvesting can start in Month V/August, not in Month VII/October, which is the usual beginning of the harvest period (see Dossier A.1.1.17). It seems, therefore, that, strategically, the Babylonians at that time may have considered growing an earlier sesame crop when grain was scarce.

In addition, there is probably a difference between Akkadian ḫarpū, “early”, and ḫarBum, “ḫarBum-plough” (see below).

3.2. Sesame, a Summer Crop

The periodicity of sesame cultivation, which is a summer crop, can be summarised as follows:

- Seeding sesame: Months II/May to Month IV/July in Babylonia (except for “early” sesame, see below), and Months III/June-IV/July in Mari

- Harvesting sesame: references from Month VII/October to Month VIII/November (see Dossier A.1.1.17).

- Work on sesame fields took place between the sowing and harvesting periods. It can be deduced from these dates that the sesame harvest took place 3 to 4 months (on average) after sowing, which is in line with studies on sesame cultivation: the plant maturity varies from 70 to 180 days according to Bedigian (Bedigian 2010: 34). Bedigian (Bedigian 2010: 10) notes more specifically that “sesame plants are harvested 75-150 days after sowing, more commonly after 100-110 days”, according to ethnographic evidence.

The evidence does not allow a precise estimation of the vegetation period. Still, it shows a general consistency between the Ur III period (see Dossier A.1.1.04 and Dossier A.1.1.10) and the Old Babylonian Period within a very rough time frame.

3.3. Sesame Cultivation from the Perspective of Barley Cultivation

Sesame cultivation was done as a filigree of barley cultivation, a winter cereal, as a small part of barley fields was used to grow sesame. A plot of land used for barley cultivation could also be reserved for sesame, according to farming contracts (BIN 07 177, YOS 08 173). Work on sesame fields began as soon as the grain season was over. The letter AbB 14 163 from Šamaš-ḫāzir’s Archive mentions 10 būr (64.8 ha) of field (in Ašdubba[geogr=Ašdubba]) and the sesame is to be sown there, in the Larsa region (see Dossier A.1.1.16). Fiette considered that this particularly large area could not be used exclusively for sesame cultivation(Fiette 2018a: 257-258). He estimates that the area allotted to sesame must have been only about 1 or 2 ikû (3.600 m² or 7.200 m²), an assumption based on letter A 07460 mentioning 7 litres of sesame seeds per ikû. Areas of sesame fields are usually recorded in ikû, which indicates a smaller space allocated to sesame than barley, often counted in būr. However, a letter attests 2 būr (about 13 ha) of sesame field (AbB 11 116). Thus, the area under sesame cultivation in the letter AbB 14 163 could be much larger than 1 or 2 ikû.

In AbB 14 082, letter discussed above, contrary to the edition (Walther Sallaberger’s private communication), Qurdūša tells Bēlšunu that he planted sesame on 9 ikû of land and that should not be careless about growing sesame because he had no grain this year (šattam še’am ul elqe! u ana eqel šamaššammī epēšim [text corrupt] nīdi aḫim lā tarašši). It underlines Bēlšunu’s concerns about the yield of his fields and the fact that a good sesame crop can “compensate” for a poor winter cereal harvest of barley.

Sesame was mostly planted on barley fields, but a farming contract, BIN 07 177 from Šamaš-ḫāzir’s Archive, seems to mention an “orchard” (kirûm) and not a “field” (eqlum): it could suggest a form of intercropping at Larsa. Bedigian(Bedigian 2010: 9-10) showed that intercropping is possible for sesame cultivation. However, against this assumption, remark that the text also mentions “sesame fields” (a.ša₃ še.giš.i₃) and that the term kirûm is very likely not attested in the text (for more details, see the commentary of BIN 07 177). Consequently, there remains no evidence of sesame intercropping in Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian Period.

4. Agricultural Techniques and Sesame Cultivation Practices

The specific agricultural techniques for sesame cultivation in the Old Babylonian period were discussed by Kraus 1968 a, then by Mauer 1983 and finally by Stol 1985, Stol 2004, and Stol 2011. Kraus highlighted the following operational sequence for sesame cultivation, summarized by Mauer:

- 1) maḫāḫum, “to soak” (to be discussed below)

- 2) sapānum, “to flatten”

- 3) nasāḫum, “to pluck out”

- 4) mayyārī maḫāṣum, “to use the mayyārum-plough”

- 5) napāsum, “to beat out”

- 6) šumqutum/maqātum, “to allow to fall out/to fall out”

- 7) nuššubum, “to blow out”

Only stages 1), 2), and 4) of this description are of interest in this dossier (for the others, see Dossier A.1.1.17 on sesame harvest in Babylonia). An analysis of the documents from the Old Babylonian period allows us to complete this view. In particular, the administrative text AOAT 440 01 from Sippar, studied by De Graef, not only mentions different stages of the chaîne opératoire concerning these agricultural techniques but also wages for the workers involved.

4.1. Soaking Sesame Seeds to Facilitate Germination?

Soaking (maḫāḫum) is documented in the letter AbB 03 065, which states that “sesame seeds should not be soaked until you see Sirius (šukūdum)”. According to Kraus 1968 a: 116, this means that sesame seeds had to be soaked to facilitate germination and that this operation could not occur before July 12th. As Reculeau (Reculeau 2009: 28) suggested, sesame fields must be appropriately prepared before sowing the pre-soaked seeds.

However, the verb maḫāḫum is usually not related to sesame seeds but to the soil to be prepared before sowing, as made clear by Powell (Powell 1991: 161-162). For example, the text TCL 1 174 from Sippar lists different groups of workers specialised in preparing the ground before sowing barley (because the text dates to month IX/December), including 6 men during 6 days for soaking (maḫāḫum) the soil. The question remains whether, before sowing, they soaked sesame seeds themselves (a technique currently used: see Bedigian 2010: 246) or just the soil. The first assumption seems to be more likely: on the one hand, in the letter AbB 03 065 discussed before, the verb maḫāḫum is directly related to sesame. On the other hand, the soaking of seeds was a common technique in Mesopotamia: the unaddressed letter (ze’pum) AbB 14 047 shows, for instance, that garlic (numun sumsar) and white onion? (sum? sikil? sar? babbar?) bulbs had to be soaked beforehand. In the letter AbB 14 141, this operation is associated with a kind of leek (geršānum). All these plants, however, belong to the genus Allium; there soaking before planting makes sense.

4.2. Ploughing Sesame Fields

Sesame fields were deep-ploughed to prepare the area. The most common expression is mayyārī maḫāṣum[glossary=mayyāram maḫāṣum] (AbB 04 141, AbB 09 243, AbB 10 015, AbB 10 093, BIN 07 177, AOAT 440 191 2.1, AOAT 440 01), which literally means hitting the ground (maḫāṣum) of the field with a plough (mayyārum). This expression is commonly used conerning fieldwork. Ox-teams (inītum) carried out this work (AbB 04 141, AbB 04 156, AbB 12 165, VAS 16 086; see Dossier A.1.1.26).

The Royal Archives of Mari also indicate another ploughing operation related to sesame cultivation: ḫurrupum (ARM 13 039; see Dossier A.1.1.14). As discussed above, Stol 1985: 119-120 considered this verb to be a testimony to the cultivation of “early sesame”, but Mauer 1983 and Reculeau 2009: 31-32 suggested that it might be related to the ḫarpum-plough. An administrative text from Sippar (AOAT 440 191 2.1) mentions a mukīl ḫarpim, which can be translated as “the one who holds the ḫarpum-plough”. This mukīl ḫarpim is clearly different from the ikkarum-farmer in the text. However, the context of document AOAT 440 191 2.1 seems to refer mainly to barley cultivation. Thus, we cannot affirm that the mukīl ḫarpim could have been assigned to sesame. Nevertheless, the mention of the verb ḫurrupum with sesame cultivation is attested. Since sesame cultivation took place in the background of barley cultivation, it is not easy to determine whether there was a specification of tasks among workers; for an analysis of the sesame workforce and their status, see Dossier A.1.1.26.

4.3. Soil Loosening of Sesame Fields

Always according to AOAT 440 191 2.1, sesame fields were loosened3Lines 1-3: eqel šamaššammī ša mayyārī mahṣu u ippašru.. De Graef (2018) showed from the text UCP 10 94 that loosening probably occurred between “ploughing” (mayyāram maḫāṣum) and “harrowing” (šakākum; see below) the fields. This text, actually related to barley cultivation, mentions 17 days of ploughing, then 2 days of “loosening” (pašārum), before 9 days of harrowing, and finally 10 days of preparing the field for the third time (De Graef 2018).

4.4. Harrowing Sesame Fields

The soil in sesame fields had to be harrowed (šakākum; AbB 09 243, AbB 10 093), which means levelling the ground and spraying clods from ploughing to prepare the soil for sowing.

The letter AbB 09 243 highlights part of the sesame cultivation process: first, the field was “ploughed, then harrowed, and finally prepared” (l. 8-10: (ša) maḫṣu šakku u šipram [ep]šu) before sowing sesame seeds. The letter CUSAS 36 137 reveals that a wet field could be cleared of weeds (kasāmum) and harrowed (šakākum4Lines 32-34: eqlam riṭibtam mala īliam aksum u aškuk.). Then, the letter indicates that the sesame field was levelled (sapānum), which in this context corresponds to the actual sowing of seeds in the ground (see below). Mauer noticed that the verb “to hoe” (rapāqum) is attested in the letter HE 123 in a sesame cultivation context.

4.5. Sowing Sesame Seeds

Little quantitative information on the number of seeds sown per field is available in the Old Babylonian documentation. However, we can deduce some ratios: thanks to the letter A 07460, we know that 7 qa (7 litres) of sesame seeds were sown by ikû (3,600 m²) in Babylonia. In Mari, 4,000 qa (4,000 or 2,000 litres) of sesame seeds were used for planting a surface area of 800 ikû (2.88 ha) with the rate of 5 qa (5 or 2.5 litres) of sesame seeds per ikû ((Chambon 2008)).

There is no specific work for “sowing”; in fact, sowing is referred to by the generic term “to cultivate” (erēšum) or the literal expression “to do sesame” (šamaššammī epēšum), as discussed above. In the Royal Archives of Mari, the term gamārum, in the context of sesame cultivation, means “to finish (seeding)” (ARM 26/1 094; see Dossier A.1.1.14). It seems that the Akkadian term for flattening a field (sapānum: see below) corresponds to the fact that the seeds have been sown, and then the area has to be levelled.

As Mauer (1983) noticed, there are no specific instructions in the Old Babylonian texts regarding the actual planting of sesame.

4.6. Flattening Sesame Fields

The verb sapānum[glossary=sapānum] is well attested to designate the flattening of sesame fields (AbB 04 156, AbB 10 193, AbB 14 055, AbB 14 163, CUSAS 36 137, MDP 23 218, MDP 23 234, YOS 08 173). Moreover, this term seems to be only used for sesame cultivation, according to the CAD S, s.v. (but the proposal to translate the verb as “to seed” should be dropped: see Reculeau 2009: 26). It is significant because it must be a technical operation specific to sesame cultivation, not related to barley cultivation. Flattening sesame fields probably corresponds to sowing the seeds and then levelling the ground, so they are protected, and a successful seeding is guaranteed.

Remark that the verb sapānum is also attested in the Royal Archives of Mari in a craftsmanship context, in which specific technical operations are discussed, dealing with metal and stone. In the letter ARM 13 017, the administrator Mukannišum tells King Zimrī-Lîm that bronze veneers had been coated with glue and “flattened”5Lines 14-16: ruqqū ša siparrim šamtū u ana sapānim qātum šaknat; Durand 1997 translated ana sapānim qātum šaknat as “on a commencé à les presser (sur les surfaces où il faut les coller)”. to shape a wooden covering (erēmum). In the administrative text A.4704, cracks in a stele must be “flattened” with lead6Lines 1-3: abārum ana sapān nakpī ša nārim; Arkhipov 2012 translated the expression as “pour abolir les fentes de la stèle”.. The letter A.2597, addressed to King Yasmaḫ-Addu, specifies that a statue is poured and they started to “flatten” it7Lines 35′-36′: ṣalmum patiq u ana sapā[n]i[m] qātum šaknat; Guichard 2019 translated sapānum in the context as “polir”.. From these occurrences, we can deduce that it is probably about filling holes/smoothing the surface of an object. The meaning of sapānum in a craft context is likely similar to its significance in agriculture, where it concerns “smoothing” and “flattening” the previously sown field.

According to the letter AbB 14 061 (reign of Rīm-Sîn I), water prevented the proper settling of the sesame seeds in the field. Instead of the 10 ha of “flattened” sesame fields hoped for, there were only 4, implying a loss of 60% of the expected area. Given the period during which the sesame field was “flattened”, this could correspond to spring flooding, which could sometimes be devastating for fieldwork. However, the sender of the letter mentions that the sesame “looks very good” (mādiš damiq), which gives an appreciation of good vegetation work. In any case, the fact that there was a loss compared to expectations might lean towards the idea that sapānum would mean ’smoothing‘ the surface of previously sown soil.

4.7. Growing Season

4.7.1. Irrigating Fields

After properly preparing and sowing the ground, it was necessary to irrigate the sesame field. Even if sesame is not a water-hungry plant, textual occurrences show that sesame fields had to be irrigated, even light (see, for example, AbB 09 078).

The expression mê qāti šaqûm in the text BIN 07 177 is unclear: does it mean “with water at hand/in control”? Does this mean a simple watering could be sufficient? In any case, it implies that farmers who worked sesame had to irrigate the field. Another letter, AbB 10 071, refers to someone who “let the water flow” (mê petûm, literally “to open water”) on the sesame field. „Artesian“ irrigation, according to Reculeau 2009: 32, consists of digging a well (AbB 13 065, YOS 12 543), but the Artesian spring is not attested in Babylonia to our knowledge.

4.7.2. Height of Sesame Plants during Cultivation

The letter AbB 01 033 (l. 18-19) gives a description of sesame plants on the field before the harvest: the sesame “is high as a poplar” (šamaššammū kīma adarim arrakū) and looks “very good” (mādiš damqū). It seems to indicate that the harvest is ready to be carried out.